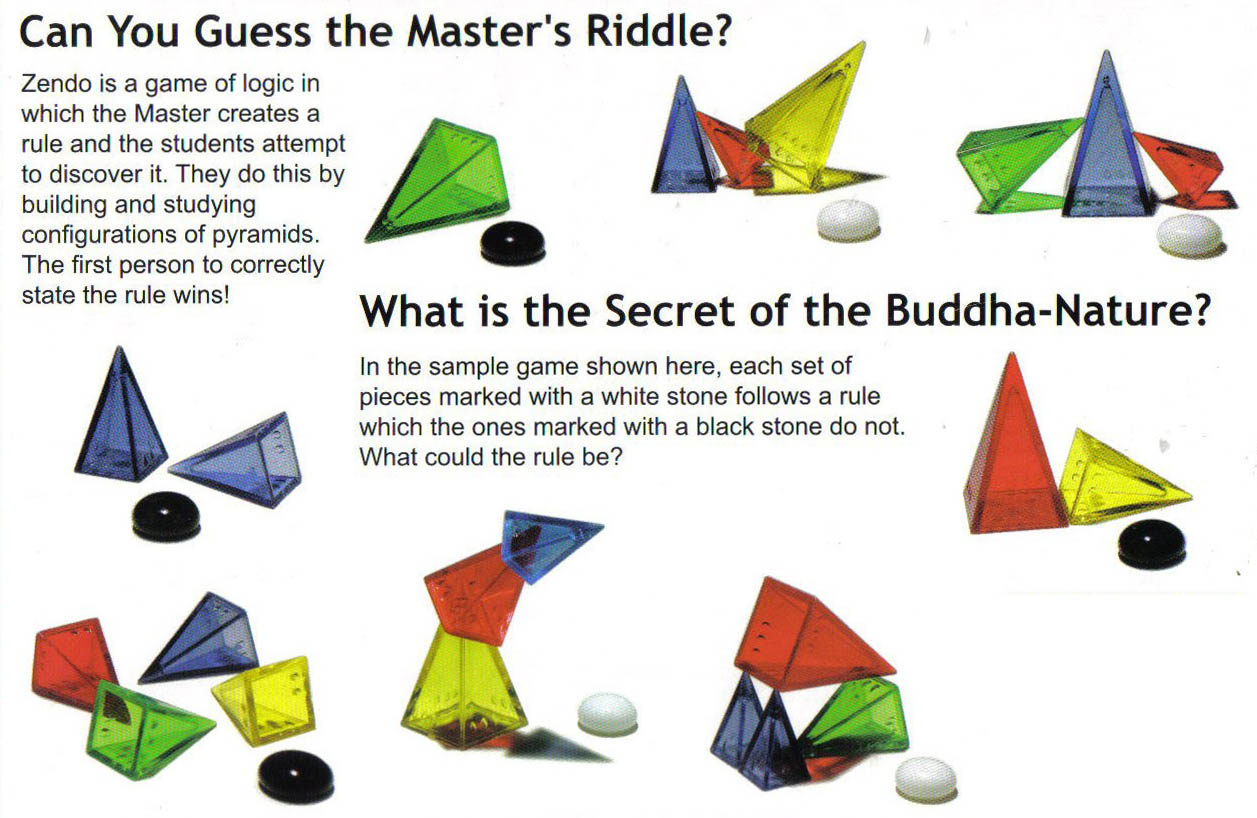

When you are selected to be the Master for a game of Zendo, you take on a very different role than you would if you were playing as one of the students.

You will not be trying to guess the secret rule; instead, you will create the secret rule that the others are trying to guess. You will spend much of your time during the game carefully marking the koans that the players build, and setting up counter-examples to their guesses.

This may not sound like much fun, but in fact, almost all of the Zendo players I know enjoy being the Master. The challenge of coming up with an interesting and clever new rule that's neither too easy nor too hard, and the fascination of watching a group of students try to solve it, can itself be viewed as a kind of game.

In fact, I know a number of Zendo players who find being the Master more enjoyable than being a student (though I personally find them equally enjoyable).

When you're the Master, it's important for you to remember that you're not really a player; you're a facilitator. You're not in competition with the students; your main objective is simply to provide an enjoyable playing experience for everyone. There are a surprising number of pitfalls along the path to this goal; the aim of this chapter is to provide you with some tips on avoiding these pitfalls and becoming a true Zendo Master.

Creating a Rule

One of the most important choices that you must make when you are the Master occurs before the game even starts-the choice of what rule to use. The most common mistake that beginning Masters make is to create rules that are too difficult for the current group of students.

Remember, your goal as Master is not to stump the students with a really tough rule-it's to provide them with an enjoyable experience. Most people don't enjoy trying to solve rules that are too difficult, and when you make a bad choice, they'll let you know about it.

Even experienced players will have a hard time estimating the difficulty level of a rule they've never tried before. The best rule-of-thumb is to remember that rules are usually more difficult than they sound. If you are trying to decide between a few different versions of a rule, go with the one that seems the simplest. It's much better to choose a rule that's too easy than one that's too difficult.

An easy rule will still be fun, and the game will probably be over quickly, at which point you're ready to simply start another. In contrast, a rule that's too difficult will generate a long and frustrating game-a punishing experience for both Master and student. My advice is to start with rules that seem stupidly simple, and work your way up slowly until you find a level that everyone's comfortable with.

Remember that what counts as "too difficult" depends not only on the experience level of your current group of players, but also on what they're currently in the mood for. Don't be afraid to discuss rule difficulty with them before you choose a rule. Ask them what kind of rule they feel like playing; if they're in the mood for a tough one, they'll tell you. On the other hand, they may not want to know what difficulty you're choosing. They'll tell you that, too.

The second-most common mistake that new Masters make is to choose a rule that's ambiguous or ill specified. You should try to think about all of the possibilities before you actually start playing the game. If you make a rule like "a koan has the Buddha-nature if it contains a large piece stacked on top of a medium piece", you should decide beforehand whether or not a large piece lying on its side with a medium piece inside it counts as a stack; it's dangerous to make this kind of decision "on the fly'; in the middle of a game.

You may sometimes be tempted to change a rule in the middle of a game, perhaps in the attempt to salvage a rule that's turning out to be too difficult. This is not a good idea. Not only does your new rule have to match everything on the table, but it also has to match everything that's ever been on the table at any point during the game. Unless you have a phenomenal memory, it will be difficult to guaran- tee that your new rule matches everything that's happened in the game so far. My advice is: understand your own rule completely before the game even starts, and never alter it once the game's in motion.

Of course, many rules do require you to make judgement calls during the course of the game, but those aren't judgement calls about the rule itself. These judgement calls are about individual koans, in which pieces are just barely pointing at other pieces, or just barely touching them, and so on.

Building The Initial Koans

After you come up with a rule, your next task is to build two initial koans-one that has the Buddha-nature according to your rule, and one that does not. How you choose to build these koans is up to you, and is largely a matter of personal style.

When you first play as Master, you may have the impulse to build large, complex initial koans, so that you will not "give too much away' before the game even starts. As you gain more experience playing Zendo, you will see that this is not necessary. It is impossible to give away any rule with only two koans, no matter how you choose to build them.

Remember that your rule seems obvious to you, because you already know what it is. The students will need many more than two examples of koans in order to see the patterns that seem obvious to you. Building large initial koans only serves to make the beginning of the game tedious, as the students reduce the sizes of those initial koans to manageable levels. My own preference is to build initial koans that contain between one and four pieces.

Selecting The First Student

After you set up the initial koans, you must select a student to go first. It really doesn't matter who you select; there's no first-player advantage in Zendo. By the time it matters whose turn it is, you'll be deep into the mid-game.

Marking Koans

As the Master, your most important responsibility during the main portion of the game is simply to mark koans correctly. A single misnarked koan will probably ruin the game, unless you catch it immediately. It's nearly impossible for students to mentally backtrack and undo the damage caused by faulty information. The best thing you can do to avoid this is to be careful.

Don't move too fast; think about every new koan the students make, and be sure you're marking it correctly. Use the "down time' while students are thinking to scan the table for possible mistakes. If you do find that you've make a mistake (and you will make a mistake eventually, if you play as Master often enough), be honest. Let all of the players know which koan you've mismarked, and let them decide how they want to handle it. They may choose to keep playing with the corrected koan. In our group, we usually prefer simply to scrap the game and start a new one.

A different kind of mistake that the beginning Master often makes after a student builds a koan is to accidentally grab the marking stone before the student calls "master' or "mondo'. This basically forces the student to call "master' (since everyone has now seen the answer). Therefore, train yourself to listen for "master' or "mondo' before you ever reach for the marking stones.

Yet another issue that arises during the marking of koans is that it's possible to "give away' certain facts about your rule by the way you study new koans. For instance, if your rule has something to do with "touching', the students may be able to glean this fact simply by watching you study the new koans they create.

Therefore, I suggest that you study each new koan as if all of its features mattered, no matter what your rule is. If there's a piece on the far side of a koan, and you can't tell whether it's touching some other piece or not, stand up and take a look, regardless of whether your rule has anything to do with touching. If you make this your standard practice, people will not be able to glean anything in particular about your rule from your behavior. Of course, if this kind of behavior becomes too elaborate, it begins to seem like misdirection, which should not be your goal as Master.

Your goal should not be to consciously misdirect the students; it should simply be to allow them to figure out the rule for themselves, without any overt clues from you. As with many of the issues in this chapter, how you approach this delicate issue is largely a matter of personal style.

Answering Questions About Koans

When you're deciding how to mark a koan, you may have to make a silent judgement call about whether one piece should be considered to be touching another piece, or pointing at another piece, and so on. Be careful not to indicate to the students that you're agonizing over a tough judgement call; they will most certainly be able to glean important facts about your rule if you do. The students should be responsible for noticing borderline cases, and asking about them if they feel that they may be important.

Because students are allowed to ask you about borderline cases, yet another issue arises: if you answer such a question without even looking at the koan, that tends to imply that your rule does have something to do with that feature (since you've clearly already checked).

However, if you look carefully before answering, that tends to imply that your rule doesn't have anything to do with that feature, since otherwise you would have already checked it in order to properly mark the koan. As always, use your own judgement about how to handle these kinds of issues. I person- ally always study a koan before answering questions about it, even when I already know the answers to the questions.

Finally, remember that you are only obligated to answer questions about the physical features of a koan; you are not obligated to answer questions about why a koan does or does not have the Buddha-nature.

Understanding A Student's Guess

The first thing that you must do when a student takes a guess is to under- stand the guess completely. You should not even begin to set up your counter-example until you are certain that you understand exactly what the student's guess is. You should understand the student's guess so well that you'd be able to Master a game of Zendo using that rule.

Do not hesitate to ask the student clarifying questions if there's anything you don't understand. Ask the student to define any terms that haven't already been agreed upon as standard terminology. Look for and point out any ambiguity in the wording of the guess, and ask the student to clarify.

Many people fear that such open discussion will unfairly give away too much information to the student who's guessing; however, this fear is groundless. The students will not be able to glean any clues from your questions, because you must clarify ambiguities even when they have no bearing on the actual rule.

Just as you must always answer a student's clarifying questions about the facts of a koan, you must always ask students about any ambiguities in their guesses, because it's simply not possible to provide a counter-example to a guess that you don't fully understand. In fact, it's in everyone's best interest to fully understand a guess; the other students are perfectly free to ask clarifying questions along with the Master.

Let's take a look at an example. Say that a student offers the following guess: "a koan has the Buddha-nature if the largest piece in it is red". This is an ambiguous guess, because it assumes that koans always have a single largest piece. It fails to specify how a koan with two or more largest pieces should be marked. In Zen parlance, the answer to such a guess is neither "yes" nor "no"; it's "mu": "unask the question".

In such a situation, your only recourse as Master is to point out the ambiguity and ask the student: do you mean, "a koan has the Buddha-nature if all of the largest pieces are red", or "a koan has the Buddha-nature if any of the largest pieces are red"? Some people are bothered by the fact that you, as the Master, seem to be "helping" the student formulate a guess.

However, it's important to understand that you haven't given the student any extra clues about your own rule; all you've done is pointed out possibilities that were already inherent in the student's original guess. Your question does not imply that one of the two possibilities is correct; they could very well both be wrong.

There's no reason not to allow the student to make this judgement call after being questioned. Indeed, the student is allowed to reconsider the guess and take the stone back at that point. A student has not officially taken a guess until an unambiguous rule has been stated and you have indicated that it's incorrect by providing a counter-example.

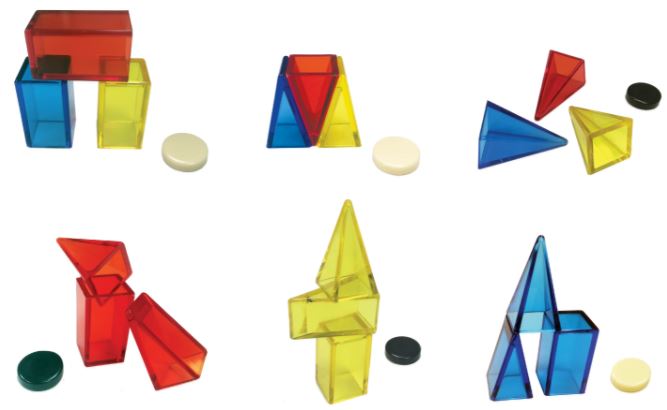

Responding To A Student's Guess

After the student has settled upon an unambiguous guess, your task is to provide a counter-example which shows why that guess is incorrect (assuming that it is). This is probably the most complicated task that you must undertake as Master; you must have a clear conception of both your own rule and the rule that the student has proposed, and you must figure out a specific way in which they are different.

Start by imagining different koans, and thinking about how the student's guess would mark them; then think about how your own rule would mark them, and find one that doesn't match. A common exchange tends to occur when Masters set up counter-examples:

- Master: "According to your guess, this koan has the Buddha-nature, correct?"

- Student: "Correct".

- Master (marking the new koan with a black stone): "Well, in fact, it does NOT have the Buddha-nature".

Many new Masters forget the crucial fact that you can disprove a guess in two ways: by building a koan that has the Buddha-nature but the student's guess says does not, or by building a koan that does not have the Buddha-nature but the student's guess says does. For instance, if a student guesses that "a koan has the Buddha-nature if it contains at least one red piece", you can disprove this guess in two different ways: you can build a white koan that contains no red pieces, or you can build a black koan that contains red pieces. Either one of these possibilities will show the student that the guess is incorrect.

Of course, there are times when only one of these methods will be possible, and this fact often confuses new Masters. For instance, suppose your rule is "a koan has the Buddha- nature if it contains more red pieces than blue pieces", and a student guesses "a koan has the Buddha-nature if it contains red pieces".

You cannot disprove the student's guess by building a white koan that contains no red pieces, because, under your rule, there are no such white koans. In a way, the student's guess is half-correct. However, you can disprove it by building a black koan that contains one red piece and one blue piece. This koan does not have the Buddha-nature according to your rule, because it does not contain more red pieces than blue pieces, but it would be white according to the student's guess, since it does contain a red piece.

There are a few common mistakes that you might make when setting up a counter-example. For instance, you may set up your counter-example and say "according to your rule, this has the Buddha-nature, correct?", and the student may say "no, my rule says that it doesn't have the Buddha-nature, and here's why..".

Usually this indicates that some kind of miscommunication has occurred between you and the student; at other times, it's simply an error on your part. (It's conceivable the student could actually be trying to cheat by changing the guess in midstream, but I have never seen this happen, and I don't believe an entire group of players could be fooled by it.

But this is yet another reason why it's important to make certain that you-and the entire group of students-understands exactly what the guess is before you set up your counter-example. If you ever suspect a student of cheating in this way, you always have the prerogative as Master to take the student's stone and let your counter-example stand).

A similar mistake occurs when you set up a koan that's (say) white according the student's guess, and then you realize that it's actually white according to your rule, too. Oops! While mistakes like these will probably not ruin a game, they do provide an unfair advantage to the student who's guessing, because they provide an extra and potentially important piece of information that the student was not supposed to have.

If that student has another stone, this new information may prompt him or her to take another guess and win the game. Misunderstandings and mistakes are impossible to eliminate completely, but expect grumbling from the other students when they occur.

There are many different ways to word any rule, and sometimes it's difficult to sort out whether or not a student's guess is identical to your rule. Zendo has been designed so that you will never accidentally declare a player's guess to be incorrect when it is in fact correct (because the only way to declare a guess incorrect is to provide a counter-example).

However, it is possible to accidentally declare a guess correct, when in fact it's actually incorrect. When this happens, someone usually notices after the fact that the two rules are actually different, and a counter-example could have been constructed. Obviously, it's impossible to recover from such a mistake, since you've already told everyone your rule.

You may take a small consolation in the fact that, since the two rules were so similar, the game was probably about to end anyway. Nevertheless, you should be on your guard against this common mistake, as it does more or less invalidate the game, even when it's obvious who "would have won".

Helpful Masters and Tight-Lipped Masters

One of the things to keep in mind when you set up a counter-example is that you have a fair amount of control over how much information your new koan provides. This is an area in which your responsibilities as Master are very open to personal interpretation and style.

On one extreme, you may choose to set up helpful counter-examples that lead the students away from error and toward the correct answer. On the other extreme, you may take the tight- lipped approach, building counter-examples which give away as little as possible, and perhaps even mislead the students, or reinforce "superstitions" that they've developed.

For instance, let's say that a student guesses "a koan has the Buddha-nature if it contains a red piece pointing at a green piece", when in fact your rule has nothing to do with red pieces, green pieces, or pointing. You could choose to build a very helpful counter-example, by (say) setting up a white koan consisting of a single yellow piece, which will strongly indicate to the student that the rule has nothing to do with any of those things.

Alternatively, you can take the tight-lipped approach, and build a complex black koan containing many pieces, including a red piece pointing at a green piece. This doesn't tell the students much at all, and may leave many of their "superstitions" about color and pointing intact.

The important point here is that you are under no obligation to be helpful or tight-lipped as a Master-this is a matter of personal style. The only official requirement is that you set up a new koan that definitively disproves the student's guess.

However, I do strongly recommend that you be consistent. Over the course of a single game, choose a style and stick with it. Being helpful gives a slight advantage to the student who's guessing, because that student has the first chance to guess again using the new information.

This is perfectly fair, as long as you're consistently helpful after all guesses. However, if you're helpful sometimes, and tight-lipped at other times, you'll be providing an unfair advantage to the students who are lucky enough to get the helpful counter-examples. Of course, even when you've chosen to be tight-lipped, a particularly incisive guess may force you to build a very helpful counter-example. In that case, the guessing student deserves the resulting advantage.

Giving Hints, and Giving Up

There is one situation in which it may be acceptable to switch from "tight-lipped" to "helpful" in the middle of a game-when it's starting to look like the rule you've chosen is too difficult, and the students are clearly ready for some hints. The least intrusive way to give the students hints is to build helpful counter-examples.

You'll notice that, as students continue to struggle with a rule that's too difficult, they'll gradually begin working together, until the game becomes a kind of group effort, with people giving each other suggestions and telling each other their theories. In such a situation, people are unlikely to be bothered if you "unfairly" switch into "helpful" mode.

In fact, at some point, the students may, individually or collec- tively, begin asking for hints. This is a delicate situation, as not all students may desire hints. As always, you must use your best judgement to assess the situation, and decide whether or not to offer a hint, and what kind of hint to offer.

At some point, students will simply not want to continue playing, and at that point they'll have to decide when it's time to give up and have you tell them your rule. Once again, be sensitive to how all the players feel; one or more players may prefer to continue to try to figure it out for themselves, even if the others quit. Do the best you can to make all players feel good about the outcome.

Yes, Tell: If your players do give up, you might be tempted not to tell them what the rule was, perhaps planning to save it for another occasion. In my opinion, this is unacceptable.

For the students, giving up is the least satisfying way to end a game of Zendo, and it almost always indicates that you've made a mistake-you've chosen a rule that's too difficult. Struggling through a too-difficult rule can be a punishing experience for the students; don't make it worse by refusing to provide them with the closure of knowing the rule they worked so hard on! Tell them what your rule was. Consider that your penance.

Continue Reading